Unilateral Contracts, A Complete Guide [2026]

Unilateral contracts may not be common as the bilateral ones, but you see them in everyday life more that you think. If fact, the whole insurance industry is based on the unilateral contracts. Bonus programs, rewards, commission-based works, and real estate open listing are other examples of the unilateral contracts. In this post, we cover everything about this type of contract, and answer the most common questions about it. So, let’s dive right in.

- What is a Unilateral Contract?

- Key Characteristics of a Unilateral Contract

- Unilateral Contract vs. Bilateral Contract

- How Unilateral Contracts Work?

- Unilateral Contract Examples in Practice

- What Happens in Case of Breach in a Unilateral Contract?

- Can you Modify a Unilateral Contract After the Offer?

- What Is an Implied Unilateral Contract?

- FAQs

Unilateral contracts may not be common as the bilateral ones, but you see them in everyday life more that you think. If fact, the whole insurance industry is based on the unilateral contracts. Bonus programs, rewards, commission-based works, and real estate open listing are other examples of the unilateral contracts. In this post, we cover everything about this type of contract, and answer the most common questions about it. So, let’s dive right in.

What is a Unilateral Contract?

A unilateral contract is a type of legal contract where one party (offeror), makes a promise to perform an action or provide something of value only if the other party (offeree), completes a specific act or performance.

In simpler words: A unilateral contralegal intect is a promise that becomes legally binding when someone performs a specific action.

Key Characteristics of a Unilateral Contract

All unilateral contracts have 5 important criteria:

1. Legal Intention

Legal intention separates true offers from empty gestures.

Just like any legit contract, a unilateral contract only counts if there’s a clear intention to create legal ties. That means the offeror has to show, either explicitly or by context, that they intend their promise to be legally binding, not just a casual or promotional statement.

In the case of unilateral contracts, courts usually read between the lines. Say a company flashes a big public offer, like a reward, bonus, or incentive, the assumption is that they’re serious. If someone does what’s asked, the company’s expected to pay up. No take-backs.

But if someone casually mentions a promise over cocktails or makes an offhand comment at a dinner party, don’t expect a judge to take that too seriously. For a unilateral contract to actually work, the offeror’s intention to be legally bound needs to be obvious-obvious enough that any reasonable person would view it as a real commitment, not just a casual talk.

2. Offer and Acceptance

The offer in a unilateral contract is basically a promise. It needs to be crystal clear, specific, and properly communicated. It shows exactly what you need to do and what you’ll get in return. But here’s the twist: the offer doesn’t become binding just because someone hears it. It only locks in once the offeree actually does the thing being asked. And there’s typically no need to inform the offeror in advance, unless the offer explicitly asks for notice.

When someone begins acting on that promise, it would be unfair for the offeror to withdraw. Then, the promissory estoppel principle may apply here. This principle protects the offeree from being left empty-handed after reasonably relied on the promise, even if the job’s not totally done yet.

In case of acceptance in the unilateral contracts, forget signing papers or exchanging pleasantries. Simply put, the contract is accepted once the person does what was asked. The moment someone does the task, that counts as acceptance. Courts deal with this all the time, especially in public reward cases.

💡 Good to Know: In U.S. contract law, the Restatement (Second) of Contracts §45 addresses this by saying that when someone is invited to accept by doing something, an option contract forms the moment they start. Meaning, once you begin performing, the offeror cannot suddenly back out. The deal is on.

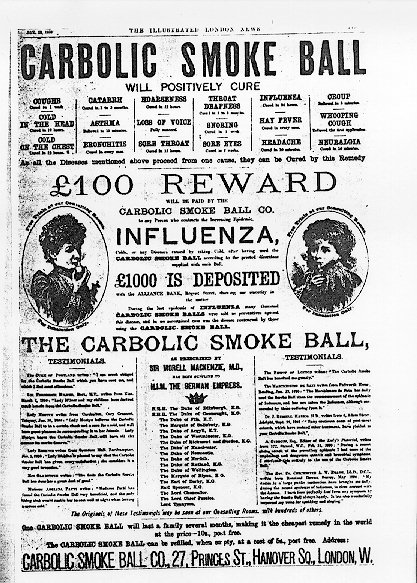

🔦 Legal Spotlight: Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co.

In 1893, an interesting case of a unilateral contract in UK made it into spotlight: Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. The story began when the company advertised a £100 reward to anyone who used its product as directed and still caught influenza, a clear one-sided promise. Mrs. Carlill used the product, got sick, and claimed the reward. When the company refused, she sued and won the case. The court ruled that her performance of the conditions (using the product and catching the flu) counted as acceptance of a unilateral offer, even though she never communicated with the company beforehand. This case shows that how a unilateral contract becomes binding through the offeree’s completed action, not through a mutual exchange of words.

Source, Wikipedia

3. Consideration in a Unilateral Contract

In a unilateral contract, consideration comes from the act performed by the person accepting the offer. It’s not about making a promise in return, but about doing what’s been asked. It’s important that this act isn’t something the person was already legally required to do.

Let’s say someone offers $500 to anyone who paints their fence. If you decide to do it, your action, painting the fence, counts as consideration. That performance is what turns the offer into a binding contract. Once you’ve done what was asked, the person who made the offer is legally obligated to follow through on their promise.

4. Revocation of Unilateral Contracts: Rules and Exceptions

Generally, a unilateral offer can be revoked any time before someone starts doing the thing. But once performance begins, many courts say the offeror can’t just bail.

🔦 Legal Spotlight: Daulia Ltd v Four Millbank Nominees Ltd

In this case, Daulia Ltd was looking to buy property. The seller, Four Millbank Nominees Ltd, made a verbal promise to enter a formal contract if Daulia showed up with a draft contract and deposit. Daulia followed the plan and came ready to finalize the deal, but the seller backed out. The court had to decide whether that was fair game.

The court made it clear: while it is acceptable to revoke an offer before the other side starts, once someone begins acting on it, like showing up with paperwork and money, the offeror cannot just pull the plug. There is an implied promise not to block the offeree from finishing the task. The takeaway is that once performance begins, the offer becomes legally binding.

5. No Obligation Until Action Is Done

Until the job is done, there is no binding contract. The offeror retains flexibility and is not legally bound until the offeree completes the requested performance.

Take a reward offer for catching a criminal. The person making the offer owes nothing until someone actually provides information that leads to the capture. No results mean no contract.

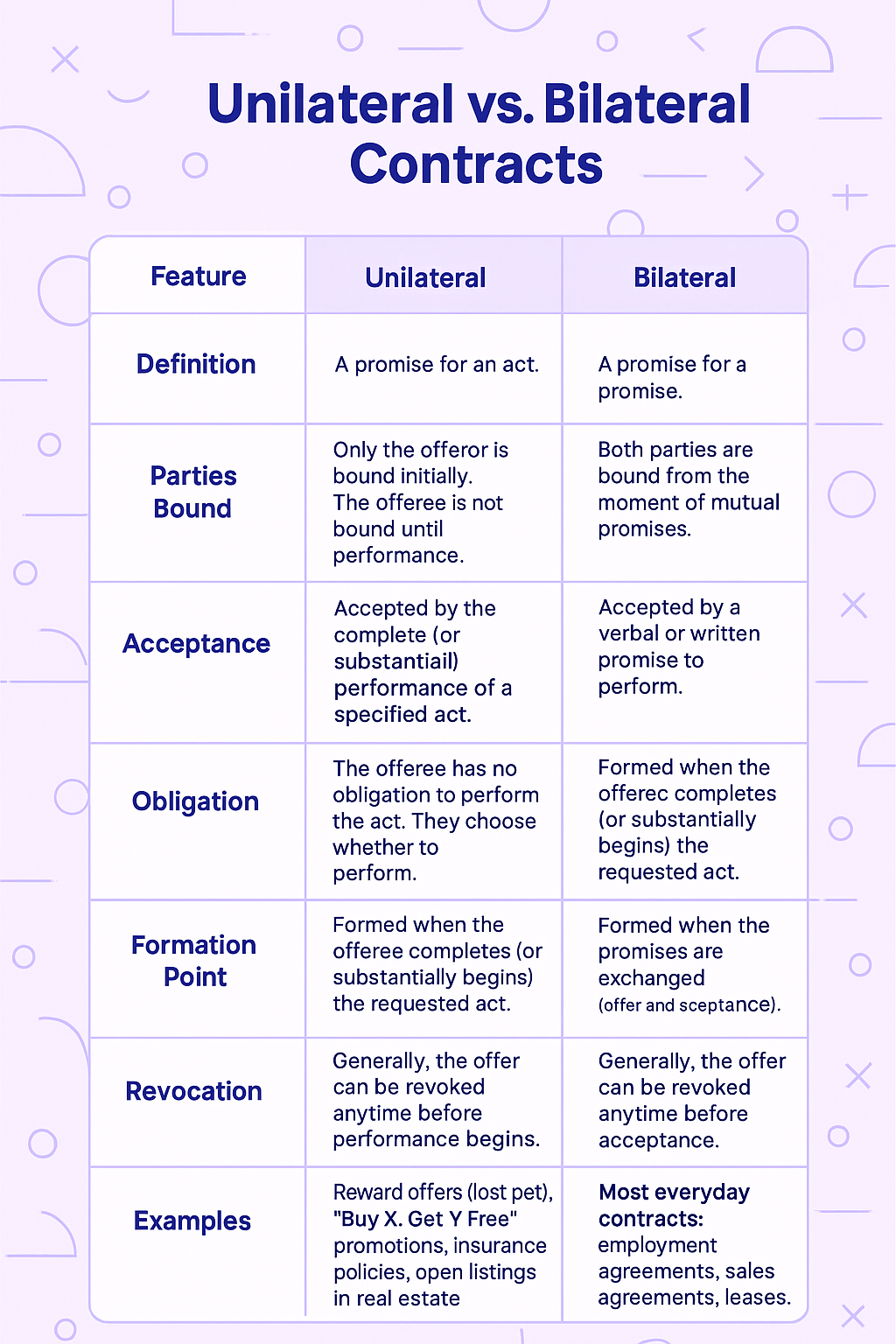

Unilateral Contract vs. Bilateral Contract

Unlike unilateral contract that only one party makes a promise, in bilateral contract, both parties make promises to do something in the future.

Examples:

Unilateral Contract: If you find my dog, your award is $100.

Bilateral Contract: You must deliver a design by next week, so I’ll pay you €500.

Unilateral vs Bilateral Contract

How Unilateral Contracts Work?

Let’s use a real estate example to see how exactly a unilateral contract works. Suppose a property developer is urgently looking to purchase land in a certain district. They draft and publicly distribute a written unilateral contract, posted online and mailed to local agents and brokers. The offer reads:

“We agree to pay a one-time fee of $25,000 to the first individual who introduces us, in writing, to an owner of at least 5 contiguous acres of land in X District, which we subsequently acquire as a result of that introduction. This offer is valid until December 31, 2026.”

This written agreement is a classic unilateral contract. The property developer is making a formal, legally binding promise, but no one is asked to sign or commit in return. The offer is open to anyone and is enforceable only upon performance.

Here’s how this works in practice:

Step 1: The Offer Is Made

A company announces in writing that it will pay a reward to anyone who introduces them to a landowner with a large property, but only if the company ends up buying that land. The offer includes clear rules, a deadline and it is obvious that the company has a clear intention to form a unilateral contract. No one is asked to sign anything. It’s open to anyone who wants to act on it.

Step 2: No One Is Forced to Act

People who receive or see the offer don’t have to do anything. If they’re not interested, they can just ignore it. There’s no contract yet; therefore, no obligation and no consequences.

Step 3: Acceptance Happens Through Action

Someone spots the offer and knows a landowner with qualifying property. They introduce the landowner to the company. A few weeks later, the company purchases the land. The person who made the introduction did not sign anything or formally accept the offer. They simply acted.

Step 4: The Contract Becomes Binding

Once the land is acquired and the person can prove they facilitated the introduction, they request the payment. If the company refuses, they have legal grounds to enforce the promise in court.

Unilateral Contract Examples in Practice

Unilateral contracts are less commonly used than the bilateral contracts, but here and the, you’ll see them in different shapes, such as:

- Reward Offers: A sign says, “$500 for the return of my lost dog.”

- Commission-Based Work: A freelancer is offered commission only if they generate a successful sale or lead.

- App Referral Programs: An app states: “Refer three friends and get a $25 credit.”

- Option Contracts (Real Estate): An investor pays a small fee for the right to buy a property within 90 days. The seller is bound to sell if the buyer decides to act, but the buyer has no obligation to follow through.

- Contests & Public Challenges: A company offers a cash prize to anyone who can solve a specific technical problem or invent a new product.

- Open Listings (Real Estate): A property owner tells several agents, “If you bring me a buyer and I sell through you, I’ll pay your commission.”

- Finder’s Fee Agreements: A company promises a fee to anyone who introduces them to an off-market property or business opportunity they later acquire.

- Life Insurance Policies: An insurer agrees: “If you pay your premiums, we’ll pay your beneficiary when you die.” The insured doesn’t promise anything beyond paying the premium.

- Sales or Performance Bonuses (Employment): A company says: “We’ll pay a $10,000 bonus to anyone who closes 12 new clients this quarter.”

- Government Rebate Programs: A city offers: “Install solar panels and receive up to €2,000 in rebates.”

- Scholarship Competitions: A foundation invites students to submit essays, stating: “Winners will receive €1,500.”

What Happens in Case of Breach in a Unilateral Contract?

A breach of contract in a unilateral contract usually happens when the offeror refuses to follow through after the offeree has done the required act. Since the contract becomes binding when the act is completed, the offeror is legally required to deliver what was promised, whether it’s money, a reward, or some other benefit.

Say someone promises $500 for the return of a lost dog. You find and return the dog as instructed, but they refuse to pay. That’s a breach. You held up your end, so they must too.

Remedies for Breach of a Unilateral Contract

If a breach is proven, the injured party can seek different breach remedies depending on the situation and local laws.

If a breach is proven, the injured party can seek different remedies depending on the situation and local laws.

1. Damages (Monetary Compensation)

This is the most common remedy. The court may order the offeror to pay the promised reward or the monetary equivalent of what was promised.

- Compensatory damages: Cover the actual loss (e.g., the unpaid $1,000 reward).

- Reliance damages (less common in unilateral cases): May apply if the offeree incurred expenses in reliance on the offer and performance.

2. Specific Performance

Specific performance remedy is rare but possible. If the promise was for something unique (e.g., a rare item or service) and money alone isn’t enough to make things right, the court may order the offeror to deliver the promised result.

3. Restitution

If the offeree gave the offeror a real benefit and the offeror accepted or gained from it, the court might require repayment, even if the contract is disputed. This keeps things fair and prevents unjust enrichment.

4. Equitable Remedies via Promissory Estoppel

If the contract isn’t fully completed, but the offeree partially performed and relied on the promise to their detriment, a court may step in using promissory estoppel to enforce fairness, potentially awarding damages or stopping the offeror from backing out.

Can you Modify a Unilateral Contract After the Offer?

In general, no. You cannot modify the offer once someone has started performing. As we mentioned earlier, in a unilateral contract, the offeror makes a promise that is accepted only by the offeree completing a specific act, such as returning a lost item or finishing a task. Once the offeree begins performance, the offer is considered locked in. Changing or revoking it at that stage risks breaching the contract or violating basic fairness.

However, if no one has started performance yet, the offeror can change or withdraw the offer, just like with any standard offer. Any modifications must be clearly communicated, and acceptance happens only through performance of the new terms.

What Is an Implied Unilateral Contract?

An implied unilateral contract is a type of unilateral agreement that isn’t spoken or written explicitly, but is instead formed through conduct, actions, or the surrounding circumstances that clearly show a promise was made and accepted by performance.

It says implied when one party (the offeror) gives off a clear signal, whether through their actions, policies, or established practice that shows they’ll provide something if a task is completed.

Let’s say a company has a long-standing policy of paying a referral bonus to employees who recommend successful job candidates. The company doesn’t explicitly promise this in writing to every employee, but everyone knows it happens, and it’s been honored consistently. If an employee refers a candidate, and that candidate gets hired, the company may be legally bound to pay the bonus, even if the promise wasn’t formally made this time. That’s an implied unilateral contract.

🧠 Did you know? Some courts can enforce an implied unilateral contract based on reasonable expectations and customary conduct, even if no formal promise was ever spoken or written.

FAQs

- What Makes an Insurance Policy a Unilateral Contract?

- An insurance policy is a unilateral contract because only the insurer makes a binding promise, to pay for covered losses — if the insured pays their premium and complies with the policy terms. The insured is not obligated to pay, but if they do, the insurer is legally required to perform. The policy is accepted through action (payment), not through a mutual exchange of promises.

- Are Unilateral Contracts Enforceable?

- Enforceability of unilateral contracts depends on whether the offeree has completed or begun the requested act. A unilateral contract becomes legally binding once the offeree performs the act specified in the offer, not just by agreeing to it. Courts will enforce the offeror’s promise as long as the performance matches the offer’s terms. If the offeree starts performance and the offeror tries to revoke, many legal systems (like U.S. and U.K. law) will prevent revocation to ensure fairness. Performance = acceptance = enforceable promise.

- Can a Unilateral Contract Be a Third Party Beneficiary Contract?

- Yes, if the contract clearly intends to benefit a third party. In a unilateral contract, even though only one party makes a promise and another performs, a third person can still benefit from it. If that benefit was intentional (not just incidental), the third party may have the right to enforce the contract once performance is complete. If the benefit was unintentional or indirect, they typically can’t.

Please keep in mind that none of the content on our blog should be considered legal advice. We understand the complexities and nuances of legal matters, and as much as we strive to ensure our information is accurate and useful, it cannot replace the personalized advice of a qualified legal professional.

Table of contents

- What is a Unilateral Contract?

- Key Characteristics of a Unilateral Contract

- Unilateral Contract vs. Bilateral Contract

- How Unilateral Contracts Work?

- Unilateral Contract Examples in Practice

- What Happens in Case of Breach in a Unilateral Contract?

- Can you Modify a Unilateral Contract After the Offer?

- What Is an Implied Unilateral Contract?

- FAQs

Want product news and updates? Sign up for our newsletter.

Other posts in Guides

What is a document audit trail and how it work

When you’re dealing with regulated processes, contracts, or any kind of business documentation, having a clear …

How to extract and manage contract metadata with AI

Contracts contain critical information, but finding it shouldn’t take hours. Instead of manually searching …

SaaS contract management explained for buyers and vendors

If you work in SaaS, you know how quickly contracts can pile up. Each one comes with its own terms, renewals, …

Contracts can be enjoyable. Get started with fynk today.

Companies using fynk's contract management software get work done faster than ever before. Ready to give valuable time back to your team?

Schedule demo